Around the world, millions of stateless people face a lifetime of exclusion and discrimination. They are unable to vote, and often cannot access education, obtain medical treatment, travel abroad, seek a job or even buy a SIM card for a mobile phone. Although 4.2 million people are known to be stateless globally, the actual number is likely much higher as less than half of all countries collect data on stateless populations. Europe is home to more than 500,000 stateless people.

“I can’t imagine what it will be like to be a citizen, but I’d like to find out before I die, I really want the sense of belonging.” Said 70 years old Benjamin who still hopes to resolve his lack of nationality. Born in Namibia, then part of South Africa, Benjamin did not acquire nationality at birth because at the time neither of his parents had citizenship or permanent residency in the country.

His Polish-born mother had emigrated from Europe after being liberated from a concentration camp at the end of the Second World War. His parents eventually naturalized as South Africans, but Benjamin was an adult by then and initially unaware that he was a citizen of neither Namibia nor South Africa.

Benjamin was repeatedly incarcerated in South Africa before fleeing to the UK in 1973. He was detained briefly, requested asylum, but was released without immigration status. For years, he was afraid to regularise his status in the UK, fearing deportation to South Africa. During that time, he was unaware that he was stateless, but found that, over time, his lack of documentation made life difficult. He had wanted to marry a British citizen, but they were unable to.

In 2013, Benjamin learned that the UK had introduced a statelessness determination procedure, offering a route to stay legitimately. He was among the first applicants. In 2014, he was granted statelessness leave with residence for 30 months. This was renewed in 2016, and in 2019, he received indefinite leave to remain as a stateless person. He was finally able to marry. Benjamin was delighted to be recognized. But his experience was stressful, expensive, and frustrating. He has had two applications and a judicial review rejected in his quest to become a British citizen.

Nationality is a universal human right. But it is one that stateless people have been deprived of as a result of circumstances that are most frequently beyond their control, for example when and where they were born, or their gender.

In the UK, as in many other countries, statelessness lives in the shadows. It is not clear how many fall into this category. While some stateless may have had their status regularized through the asylum process, only 64 have been recognized as stateless through the Home Office’s dedicated statelessness procedure, which started in 2013. This low number suggests that more needs to be done to identify and protect the stateless in the UK.

The UK is a signatory to the two key international conventions addressing statelessness and is one of the few countries to introduce a procedure to identify stateless people. But with so few being recognized as stateless people’s lives remain on hold; they are unable to work or gain an education and live in fear of being detained or deported.

Progress in addressing statelessness globally is mixed. The resolve needed to tackle large, protracted statelessness situations has been lacking, and increased forced displacement is bringing new risks of statelessness. Since late August, for example, the Rohingya minority has fled violence and persecution in Myanmar: over 600,000 are now living in Bangladesh.

Over 75% of the world’s stateless belong to minority groups like the Rohingya, the Roma in Europe, and the Pemba in Kenya. A recent report from UNHCR showed how discrimination, lack of documentation, poverty, and fear defined the lives of stateless minorities around the world.

For many stateless people in the UK, the quest for recognition and status can be a lengthy, debilitating struggle. Through bad luck or circumstance, some in the UK find themselves citizens of nowhere. Without a nationality, they struggle for years or even decades to access services, travel abroad, or adequately support themselves.

Those interviewed spoke of their frustration and distress at the lengthy process and the limitations of their lack of status involved. Many cited a deterioration in mental health and raised concerns around the quality of reviews, difficulties obtaining evidence, the use of detention, and the overall process. Some of the stateless in the UK have found themselves without an official status through no fault of their own, the victims of administrative oversights or failures.

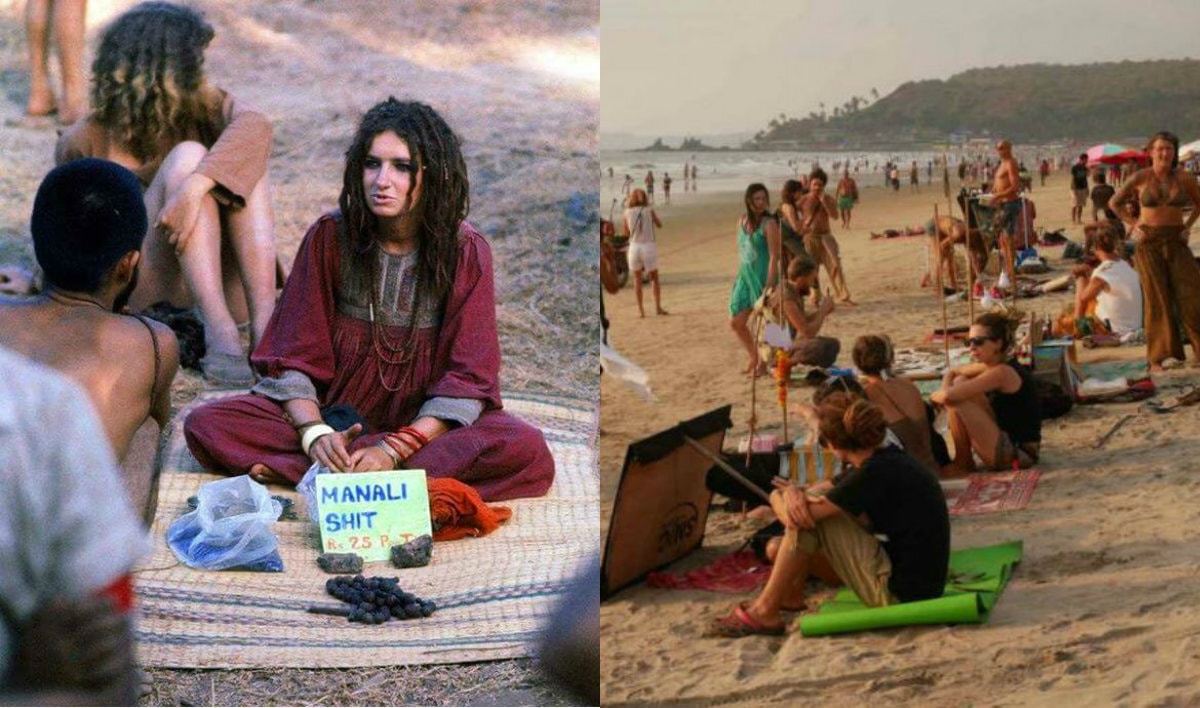

Paul was born in Goa, an Indian citizen. His parents were both British Overseas Citizens – a class of nationality granted under limited circumstances to people connected with former British colonies – and his father subsequently acquired full British citizenship.

Paul was issued a British passport in India in 2007. Believing he had acquired British citizenship, he then surrendered his Indian citizenship in line with Indian law. After receiving his British passport, Paul traveled to join his father in the UK. A few months later, the British authorities informed Paul that his passport had been issued in error, and he was not in fact entitled to British nationality. Subsequent applications to regain his Indian citizenship were rejected.

Positively, he recently obtained five years’ leave to remain after his second application for statelessness leave. Speaking before that, he described the impact of the bureaucratic “maze. It’s two steps forward, always three steps back,” he said.

UNHCR has been campaigning to improve the plight of stateless people everywhere through its iBelong campaign, which aims to end statelessness by 2024 and encourages governments to resolve existing major situations of statelessness and ensure that no child is born stateless.

UNHCR’s Representative to the UK, Gonzalo Vargas Llosa, said: The UK was one of the first countries to establish a procedure to identify stateless persons. This is an important achievement. However, it is clear that more needs to be done in the UK and abroad to ensure that stateless people are given the protection they desperately need.”